|

Marananussati

|

|

|

by |

|

|

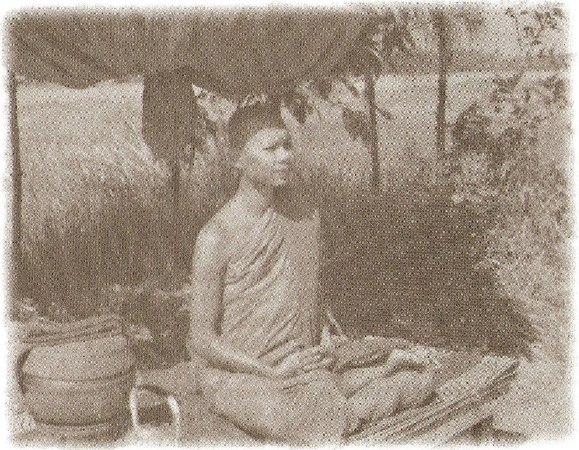

An abridged version of a farewell Dhamma desana delivered by Venerable Ajahn Anan at Wat Fah Krahm (Cittabhavanaram), Lamlukka, Patum Thani, in November 1984 (2527 BE) as he prepared to depart to continue his practice in Rayong Province at what would later become his present day residence of Wat Marp Jan. In the course of this talk, Ajahn Anan offers the details of his practice as a gift of Dhamma to gladden and. inspire all those who had provided support during the years he spent practising at Wat Fah Krahm.

"When the world seen according to reality, the Vision of Dhamma arises. This is a profound transformation. 'The heart is transformed from that of an ordinary person. It changes from a kalyanajana to an Ariyajana; from just, simply 'a good person' to a Noble One."

Today, with the permission of Venerable Ajahn

Piak and my friends in Dhamma, the time has come for me to speak about Dhamma

practice in the course of which there will be much food for thought to bring

into your own practice of meditation. Therefore, let us all be determined to

firmly compose the mind, to make it calm and peaceful by trying to focus upon

the in-and-out breathing. Meditate feeling content and at ease, allowing the

breathing to be comfortable and relaxed. Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambuddhassa Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambuddhassa Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambuddhassa Buddham Dhammam Sangham namassami

Having this opportunity to meet here today is because of our interest in Dhamma and our attempt to practise meditation in accordance with the advice and instruction of the Lord Buddha. Today then is a good opportunity for me to speak the truth about my own practice. Today seems the right occasion to speak because for all of us to be sitting here, having lived this far, is indeed a rarity. Perhaps next year, or in the years ahead, we will not have the chance to meet together or see each other again. This or that person may have left us, some to other places, some because old age prevents them from coming, and some because of death. Therefore, the Buddha taught us that our lives are uncertain; death is for sure. It is certain we must die; our lives will end in death. When we foresee the danger in life's uncertainty, we become one who is heedful.

The Buddha stated that the one who is heedful never dies. "Appamado amatapadam, pamado maccuno padam" - heedfulness is the path to the deathless; the one who is heedless is dead already. Such people, although still alive and sitting, standing or walking, are said to have already died because they are dead to virtue and to goodness, to merit and to that which is wholesome. However, all of us sitting here can be described as 'heedful'; trying to be interested and attentive in the practice of Dhamma that will brighten, cleanse and purify our hearts in accordance with our efforts. Death therefore, can become a wellspring of Dhamma. The Buddha informed us that the mind of one who frequently contemplates death will become heedful of the truth, recollecting the impermanence, suffering and selflessness of this body. Just this subject of death then, can become a basis for our meditation, a foundation for our practice that we cannot overlook.

If we frequently practise marananussati - contemplating death as a meditation theme - our minds will become heedful of life's uncertainty and the certainty of death. We have to die for sure; this life will end in death. Some people, after conception, die in the womb. Others pass away after a couple of months or a couple of years, or after reaching the age of ten or twenty. This we can observe for ourselves. Our human lifespan therefore, is uncertain. Some die young and others die old. If we contemplate death in this way, then whatever power and prestige one may possess, whatever riches, rank and renown, whether a prince or a pauper, a beggar or a billionaire, even great and mighty kings, we can see that death grants no exemptions. Even our Supremely Enlightened Lord Buddha, the Mahapurisa, The Champion of the World, the refuge of all beings, fully endowed with the virtues of wisdom, great compassion, moral discipline and absolute purity; even the life of that Sublime One's body was crushed by death. Will we then, as ordinary people not yet possessing the wisdom, purity, power and might of a Buddha, escape death and the danger inherent in death? Will we not have to be parted from all that we love and delight in? I myself will not escape death; it is beyond the ability of anyone. I consider my life to be uncertain whereas death is a certainty. Consequently, everyone in this world is in the same predicament, nobody can escape from death. Death will envelop us all, ending in separation from everything we love and cherish.

All our wealth and possessions are gained with great difficulty. Some people amass a great stash but are afraid to put it to use, whereas others are thrifty misers and horde their wealth away. When they pass on, these goods and riches are unable to bring them any benefits. Why do we act like this? Because, like children playing in the garden as a blazing fire approaches, we do not yet see the danger closing in. Most of us are like these children having fun and frolics; we are unaware of the threat, unaware of the danger closing in, creeping slowly, relentlessly upon us second by second, minute by minute, that is, old age, sickness and death. In the end, death comes to separate us from our bodies. However, it does not just part us from our own bodies; it also parts us from our children and spouses, our parents and relatives. Death separates and takes away that which we most love. How is it possible that death can take these things away from us? For the reason that these things are not within our power to control. Separation through death is a natural law; the law of death is a force of nature.

After hearing the Teaching of the Buddha, Venerable Anna Kondanna saw the truth because he understood how all things naturally arise and pass away. The meaning of 'all things' here is 'everything that exists'; everything that is subject to the conditions of impermanence, suffering and not-self, where no self or soul or person or being or ‘me' or ‘you' can be found. Venerable Anna Kondanna saw his body as impermanent, suffering and not-self, as arising and ceasing, as 'being without a Being'. When one understands these natural conditions, as did Anna Kondanna, it is called attaining the 'Vision of Dhamma', that is, he saw the physical body according to reality. When the world is seen according to reality, the Vision of Dhamma arises. This is a profound transformation. The heart is transformed from that of an ordinary person. It changes from a kalyanajana to an Ariyajana; from just, simply ‘a good person' to a Noble One. When the Dhamma is seen, it is just this Dhamma which makes the heart noble. How is it that the heart becomes noble by seeing the Dhamma? It is because of being heedful like Venerable Anna Kondanna. Before the Buddha's enlightenment, Venerable Kondanna was diligent in serving and ministering to the Bodhisatta for six years. However, after he saw the Buddha-to-be partake of nourishing food, Venerable Kondanna shunned him and ran away believing it unlikely that the Buddha would attain to any lofty spiritual realisation'. Although Venerable Kondanna renounced the Bodhisatta, he did not abandon his own practice. He was possessed of faith and having already put forth effort to build and perfect spiritual qualities, he realised that by continuing to cultivate Dhamma in this way, his heart would likely gain a firm spiritual foundation, a natural source of confidence and purity.

Therefore, I would like to encourage you all to thoroughly investigate this subject of death. The contemplation of death, skilfully cultivated as a basic meditation practice, naturally brings many benefits. All anxiety, worry and worldly concerns will inevitably be eliminated from our hearts as a matter of course. For this reason then, we should all put forth effort in our meditation and try to make the investigation and contemplation of death firm in our minds. Try to develop this meditation as much as possible, investigating with determination and resolution for the sake of results.

Sometimes, during our investigation of death, the heart experiences sudden flashes of samvega, a profound sadness with the sobering insight that life is uncertain, and that if we are destined to die, then nothing is worth clinging onto. With the arising of samvega in the heart like this, it can be said that our contemplation of the meditation theme is correct and proper. If our mind experiences sudden moments of calm which then turns into wayward thinking, this shows that the mind is concentrated to the level of khanika samadhi. If the calm in the mind goes deeper than this which, when applied to the contemplation of the meditation theme, arouses feelings of samvega and spiritual rapture - the samvega arising only momentarily leaving behind an experience of deep bliss, peace and serenity - then this indicates that the mind is entering upacara samadhi. This is a samadhi which is ‘almost solid', sustained for long periods of time and where body and mind are light and tranquil.

If we use our minds to frequently contemplate in this way, then solid concentration will arise as a matter of course. This can be called ‘cultivating wisdom to develop samadhi'. That is to say, we contemplate using the mind to see impermanence, suffering and not self; to see that this body will have to die. To arouse the theme of death in the mind, we must use our memory of those things we have heard and remembered to guide our contemplation. As the mind converges, it gradually calms down, advancing in stages from khanika samadhi to upacara samadhi. As proficiency in samadhi increases, the contemplation of death becomes more skilful and effortless accordingly.

In my own practice, I used marananussati - the contemplation of death - as my first basic theme of meditation. I made an effort to recollect death all the time. For example, sometimes I would watch children playing football, observing their delight in the world and their experience of pleasant, desirable moods. I would reflect, "These our bodies cannot be taken for granted. Do those people who come looking for entertainment and distraction realise that death is creeping up on them? I, too, am no exception. If I could die right now, or at any moment, then why do I allow myself to seek only delight and distraction in the world?"

When I opened a newspaper and saw the daily announcements that this or that person had died and that the funeral chanting would be conducted in such a monastery at such and such a time, then I would reflect that these people, although all of rank, fame and fortune, they still had to meet with death and disaster. Previously they were alive just as I am now, and in the end, like them, I naturally will have to die. Contemplating in this way, the mind became calm and samvega arose. This is called making an effort to develop the recollection of death as a basic meditation practice.

In my practice, I continually put forth effort to develop the meditation on death. For the first four years I was still developing the contemplation of death as my main theme of meditation. At the start of my fourth rains retreat, I began to investigate the aspect of mindfulness practice known as kayagata, that is, the contemplation of the body for the purpose of eliminating desire and attraction towards it. When I reviewed the body in my mind, then whichever part or aspect appeared as desirable, I would try to contemplate right there. I would pluck off the nose or ears, pop the eyes out and bash in the mouth. Whenever the eye made contact with external forms, whether my own body or those of others, I put forth effort contemplating in this way to cut off any desire. At the end of that year, following my fourth rains retreat, I began the practice of asubha kammatthana; contemplating the body from the perspective of its unattractive or repulsive nature. When on alms round in the countryside, I tried to observe people's hands, contemplating the wrinkled skin of the elderly as they placed food offerings in my bowl. I would then try to remember this image by creating a mental picture in my mind.

I made a continuous effort to practise asubha kammatthana but my meditation was still not very good until the beginning of my sixth rains retreat. At that time I began investigating the repulsive aspect of the body with earnestness. I only began seriously meditating on asubha at this time for the reason that, since ordaining, I had harboured a deepseated notion that I should not really apply myself to this practice until after five years as a monk had passed. This idea held up my practice of body contemplation. I don't know how this view became embedded in the mind like this, but it ended up going this way; after my fifth rains retreat and before the beginning of my sixth, I did start to sincerely investigate asubha following this impression. The contemplation of the skin was assigned to me as a meditation theme by my teacher with the confident assurance that this contemplation would bring the heart to liberation, quelling all greed, hatred and delusion. Initially I was doubtful about body contemplation because the traditional meditation on the thirty-two parts seemed too lengthy and cumbersome to practise. I didn't know which meditation subject was most suited to my temperament or which of these kammatthana would dispel greed, hatred and delusion from my heart. This uncertainty remained until just before my sixth rains retreat when, while sitting in meditation, a nimitta arose that made up my mind for sure. This was an asubha nimitta where the skin was seen as disintegrating, flaking and peeling away. My perception of this mental image was dependent upon the spiritual power (parami) of my teacher. Through this assistance, I was able to perceive the asubha-nimitta at that moment because having entered upacara samadhi, the heart was receptive to signs and visions.

With confidence in both the nimitta and asubha meditation on the skin established, I was unwavering in my effort to practise, firmly holding the meditation object in mind. I strove to investigate, making the mind concentrated. Sometimes I detached and peeled the skin away from the body revealing the flesh beneath. This gave rise to samvega - feelings of profound sobriety - and the mind would become still. After emerging from that state of calm, I would contemplate the skin making it shrivel up and disintegrate.

In the beginning, gradually learning to incline the mind towards contemplation is a difficult and arduous practice. When in samadhi, the mind is unified without thoughts arising; it has been stilled and brought to singleness. There is no duality, only a unified state of awareness. Through the power of concentration, I would contemplate the skin, peeling it away from the hands, feet, lips and face and change it into earth. I would break the skin into tiny pieces and turn it into earth, alter its state into that of soil.

Initially, I could only make it into earth; I couldn't break it apart any more than that. Later on, when the mind had made more progress and concentration was deeper, after turning the skin into earth, I could then make this earth crumble away and completely vanish to nothing. The investigation went from skin to soil, from dirt to dust, breaking it apart like this into what is called the state of emptiness. I could see that in this state, skin does not exist. Initially the skin existed, and then it changed its state into earth, then nothingness. The realisation then arose in the heart; skin is anatta, not a soul, not a self, it is simply empty.

When the heart realised that skin is empty, piti - spiritual rapture - arose and the body and the mind temporarily disengaged. There was awareness that the mind had disengaged and withdrawn from the body and from attachment to this physical form. Just this is magga - the path; the way of practice for the eradication of greed, hatred and delusion. Once the path is seen in this way, then greed, hatred and delusion begin to fade away because it is just this experience of magga that destroys these defilements, leaving the heart awakened and invigorated. It is like previously, we had only heard the teachers talk about unifying the mind before investigating the body but now we know for ourselves, "Oh! It's just like they said!" The heart becomes a witness to the truth, the body seen according to reality, there are no longer any doubts; this is the way! The path entering the 'stream of Dhamma' starts to become clear.

At that time however, the heart was only just beginning to recognise the path, it had not yet changed. The experience of magga here was only enough to see that this was the right way. When I practised in this way, feelings of deep rapture and contentment arose, and I could let go of the body. Great confidence arose, "This is the way all previous practitioners have come! All those who practised well came by this route!" I was absolutely certain that this was the way to liberation from suffering. Although I had only gained knowledge of the path of practice, I was still greatly encouraged.

I practised continuously, repeatedly investigating the skin back and forth. Whenever I saw other people I would always maintain silence, continuing my contemplation, keeping the mind calm and concentrated. Making an effort to restrain one's speech is essential. I am quite a garrulous person and so, during my sixth rains retreat, I tried to avoid speaking altogether. During this period, I spoke as little as possible because if I talked a lot, then the mind would not remain concentrated. Lengthy conversations would lead to much restless thinking so that when I came to sit meditation, the mind would not calm down. Therefore, I practised restraint. My teacher urged and instructed us to speak little, sleep little and eat little, but when we don't see the harm in indulgence, then practising in this way is difficult. However, during my sixth rains retreat, I saw the harmful consequences in unrestrained speech and so I put forth effort to speak as little as possible. When I spoke less and my mind was contained and composed, then samadhi was firmer. For this reason it is taught that s1a is a condition for the arising of samadhi.

When samadhi became firmer and more focused, I practised contemplating the skin as dhatu - fundamental elements - making it disintegrate into emptiness. In a short time, I became more skilful and proficient at letting go of the body, seeing it as anattam, aniccam and dukkham respectively. As I viewed things in this light more and, more with deepening profundity, my resourcefulness and understanding continuously increased. My teacher urged me to strive for proficiency in my contemplation, that is, for nothing less than expertise in the field of investigation and analysis.

I continued to practise in this way until the end of the rains retreat. However, sometimes when contemplating the skin, weariness would set in and I would have to change my practice and turn towards other objects of contemplation instead, such as the bones. Proficiency in contemplating and investigating the repulsiveness of the body increased nevertheless and subsequently, after my sixth rains retreat, on December 28th 1981, a transformation occurred.

For several days before this I had been practising restraint in speech and the mind was composed and peaceful whether walking, standing, seated or reclining. The mind was calm and unified, disinterested in thinking, whether of the past or the future. With the mind peaceful in this way, I put forth continuous effort contemplating the skin.

On 28th December 1981, I was sitting in samadhi and when the mind had emerged from its unified state, I began to contemplate the skin, peeling it away from the lips. No sooner had the skin dropped to the ground than the heart realised, instantaneously, that skin is not-self. The realisation on this occasion was unlike those gained during the rains retreat. This time, the realisation was an illumination of such profundity that the body was seen with absolute clarity as not-self, as merely natural elements, as aniccam - dukkham - anattam. When this insight arose, it was as if the mind flipped out of the body in a shattering transformation. The mind entered a state that I wouldn't know what to call. It was like falling into the current of an on-flowing river. There was awareness that the heart had entered the stream of Dhamma.

When the heart entered the stream, there was knowledge that the Dhamma had been irreversibly attained. The heart was amazingly different than usual. There were feelings of profound bliss with the realisation that all external conditions are anatta. Everything was seen as Dhamma; whatever the heart focused on, the truth would be seen. This was the experience of phala - the fruit - and remained for several days. The investigation from the beginning of my sixth rains retreat until its end was the consummation of magga - the path to this realisation.

On the 28t" December, through the realisation that the skin is aniccam - dukkham - anatta, the transformed heart also clearly saw the entire physical body in terms of these Three Characteristics. Just seeing the skin alone with insight was enough to see deeply throughout the whole body because it is of the same nature, composed of the same fundamental elements. Whatever fundamental element is seen with clarity, then the entire physical body is also clearly perceived in this light and the defilements of greed, hatred and delusion steadily diminish.

Following this, my confidence in the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha greatly increased because I had seen for myself the truth taught by the Buddha; that this body is aniccam - dukkham - anatta. I had enormous confidence in the Buddha as the teacher of the way, confidence in the truth of the Dhamma because I had realised it for myself, and faith in the Ariya Sangha as being truly well practised because my heart had also become steadfast in this way of training. Having realised this state, I understood why the scriptures say that the heart no longer falls into evil ways.

The heart was steady and possessed of enormous faith whatever the passing mood or mental state. Supposing someone was to tell me to kill an animal saying, "If you don't kill this creature then I'll murder you!" The mind, though, would have already been made up, the heart would have already come to an agreement because it has clearly seen the body as aniccam - dukkham - anattam; no longer will it permit the performance of unwholesome deeds or submit to acts of evil. The path that leads to the lower realms of torment and misery through the performance of evil, unskilful actions has been shut and sealed. How does it come to be shut and sealed? It is just this heart that seals itself off. It happens by itself because sila enters and abides in the heart. Prior to December 28th, my practice of sila was just an outward form, the use of precepts to discipline conduct in body and speech. Then on this day, the heart was transformed and the practice of sila became an internal affair of the heart. The heart became disciplined inside, able to discriminate between right and wrong without the need for external precepts. For example, sometimes I would do something wrong but with the mind calm and peaceful, it would know that that act was unwholesome. The heart had attained to balance and security and so I was always on the right path, where evil is gradually and steadily abandoned. The Buddha explained that the one who reaches this point will not be born again, or has reached a limit of only seven more births at most. On December 28th 1981, my heart plunged into the stream of Dhamma and realised the truth just as I have described here. At that moment great confidence arose in my heart together with feelings of tremendous bliss and well being.

Following on from this, my meditation proceeded smoothly without obstacles and with a clear understanding of the path of practice. I continued to strive in the investigation of the physical body, contemplating the skin in terms of its elemental properties. Through the power of samadhi focused on the body, I would cause these elements to disintegrate and vanish until the body was seen as anatta.

Sometimes in the course of my meditation, weariness with the object of contemplation would set in, and so I would change my focus. For example, if I became bored contemplating the skin on the hands, then I would move to the chest or head or imagine the skin splattered with blood, making it disintegrate and vanish, revealing its selfless nature. I needed to have flexibility as a skilful means in my investigation. This, however, is an individual matter because each person is different. I would reflect that sometimes, when investigating the same meditation theme, the heart doesn't want to do the work; it becomes dull and boring like eating just one type of food. When the heart became bored, I would have to be flexible, changing and adjusting my meditation so that the heart could see the body with insight as anatta.

As my practice approached the month of September 1982, the heart began to find deep contentment through the development of the four brahmavihara. Quite simply, I loved cultivating loving-kindness, compassion, appreciation and equanimity (metta, karuna, mudita and upekkha). My experience of these 'divine abidings' was different from before in that, although the heart often dwelt in these states, they had not as yet become a firm or constant presence. As soon as I entered September of that year however, the heart found deep satisfaction through the cultivation of these sublime emotions. Meanwhile, my investigation of the body continued with the contemplation of the blood.

One point of practice that I had to make an effort to refine concerned being reserved and restrained in speech, in sleep and in the senses. Luang Por Chah would instruct us in 'the mode of practice that is never wrong' (apannaka patipada), that is, restraining the senses from like and, dislike, restraint from overindulgence in sleep by arousing energy, and restraint in the consumption of food. I tried hard to practise in this way, making an effort to restrain my speech. This is essential because garrulousness leads the heart away from peace and causes samadhi to degenerate and without samadhi, there is no insight. I continued to strive in the way described until the end of that year, 1982.

At the beginning of the year 1983, I became more skilled in the practice of the brahmavihara. The investigation of the physical body - the kayasankhara - continued with the skin as the main theme of meditation. I strove to investigate just this single theme back and forth, shifting and alternating between the skin of the feet, head, chest, hands, lips and face. I would investigate the repulsive aspects of the female body, focusing deep inside on the intestines, kidneys, liver and lungs. Whatever devices or techniques others may have employed in their meditation, those described here were the skilful means that I used in the course of my investigation into the physical body.

I had to put forth a consistent effort, not just fits and starts. I was convinced that there was nothing higher than unremitting effort; relinquishing all in the attempt to find the time and opportunity to strive resolutely in practice. I tried to contemplate all external objects as anatta, making them vanish away. Sometimes I would contemplate those things that I used to consider valuable, such as diamonds. When they disintegrate, diamonds are no different from earth. In the mind's eye, I would change them into earth, break them down into soil and then see how this earth combined and compressed over time to form diamonds. I investigated strenuously to cut off attraction towards worldly things.

Each time I contemplated the body, any attachment towards it would be removed from the heart along with the delight that accompanies clinging to this physical form. The power of greed, hatred and delusion was steadily undermined and weakened. The heart became absorbed in the practice, blissful, tranquil and at ease. There were no feelings of weariness, only the need to practise for the sake of liberation. Sometimes if I happened to see a beautiful woman, then in my mind's eye her body would become bloated and swollen, splitting apart until it disintegrated and was seen as anatta in accordance with reality.

As my practice entered June of 1983, close to the rains retreat, a desire to accelerate its efforts arose within the heart as though it longed to be finished with its work once and for all; to go all-out in practice. There was an urgency to accelerate my efforts and diminish the power of lust, anger and delusion (raga, dosa and moha) in the heart. Consequently, I took leave of Ajahn Piak and Ajahn Dtan and went to spend the rains retreat at Ban Mee - Noodle Village. After several days at Ban Mee I began to strive in earnest until, one day, the mind became very peaceful. As I sat and focused inwards in samadhi, the heart became calm and blissful. Then it passed beyond piti and into the Second Jhana, an experience of deep serenity, bliss and one-pointedness. The feeling of piti was not the rapture of upacara samadhi but the inner gladness of jhana without vitakka and vicara, accompanied with the joy and happiness born of samadhi.

When the mind had withdrawn from this experience, I listened to a tape of Luang Por Chah teaching on the subject of existence and birth (bhava and jati). Luang Por pointed out that whatever we attach to, will define our mode of existence and subsequent rebirth, which will, in turn, be a cause of suffering. At that time, I hadn't been performing the daily monastic duty of the morning and evening chanting. The heart had no desire to chant or recite; it only wanted to increase its efforts in meditation. However, while listening to Luang Por Chah, I reflected that the reason my heart was squirming and feeling ill-at-ease at that moment was just because of this desire not to do any chanting. After reflecting in this way, the heart admitted to this truth and agreed to do the chanting. At that moment, it was as if something fell away or detached itself from the heart giving rise to a deep rapture, the heart feeling light, free and unburdened.

I felt completely immersed in bliss for the duration of that day. Around midnight or one in the morning, the mind was still wide awake despite having not slept all night . . . The fruit that arose from my practice on that occasion still remains with me right up to today. The heart became calm and peaceful with the awareness that my practice had risen to another level of freedom. After June 20th 1983 the heart began to feel relief from the defilements of lust, anger and delusion. In the period of practice between December 28th and June 20th, the heart became much more at ease than it had ever been before. The heart was deeply contented and care-free, and the practice was slowly and steadily improving, becoming easier and more thorough.

At the end of October of that year, I was continuing with the contemplation of the body as elements. On one occasion, instead of investigating the skin like before, the mind penetrated right through to the bones, seeing them disintegrate as anatta. Following on from this, I would repeatedly contemplate the body as an elemental experience of earth, air, fire and water. In a meticulous investigation of increasing refinement and profundity, the body was seen as elements disbanding and disintegrating; seen as anatta.

After contemplation as dhatu, the body would separate out into its various elemental components; fine dust, a stream of water, eddies or bubbles of air, swirling tongues of fire. As the investigation deepened from the coarse to the refined, these elements would, in turn, disband and disintegrate until the body was seen as mere atoms vanishing away, completely ending in anatta.

In order to investigate the body as elements, uproot attachment to them as self and realise anatta, samadhi must have reached the level of Third Jhana, accessing the power of sukha. In the serenity of Third Jhana, piti has been abandoned leaving only sukha and upekkha. When the mind emerges from the stillness of Third Jhana, then the investigation has the power to destroy the conditioned perception of the elements as self. If samadhi has not reached the level of Third Jhana, then the investigation will be unable to demolish and destroy the attachment to the elements as one's self. Because this defiled conditioning is deeply ingrained, it requires an equally deep samadhi before this kilesa can be destroyed. Therefore, for the investigation to penetrate deep within, it must be paired with deep samadhi.

I investigated the attachment to the elements back and forth until the beginning of January 1984. At this time the investigation turned towards those mental images and perceptions that the mind would store away as memories. For example, when the eye saw physical. forms, sanna - the memory - would make a mental note and store them away. These memories and perceptions are deeply ingrained in the mind. When I sat in meditation they would arise and reveal themselves. In my investigation, I now had to strive to purify the heart from attraction and aversion based on these memories and perceptions.

When distorted and deluded perceptions of beauty arose, the mind had to counter and undermine them by creating perceptions of the ugly and unattractive. At that time, I thought that the kilesas arose from the physical senses of the body, the eye, the ear and so forth. These various sense-bases are the focal point where arisen sense impressions are received. I believed that by getting rid of attachment to these senses, then whenever experiencing sights, sounds, smells and flavours, there would no longer be any feelings of attraction or aversion towards these sense-objects.

When I sat in meditation, mental images would arise. Pictures of those things that the heart was attached to would manifest within the mind. Some had an appealing and attractive quality to them; others were enticing and seductive, sometimes drawing the heart into strongly binding infatuations. Craving and defilement were cunningly disguised as mental images embedded within the heart. They would manifest and entice in all manner of ways. After regarding these mental images, the heart would conceive them as appealing and become attached.

When the mind had sufficient strength, the investigation would turn towards the body. Whatever part of the body would appear in these mental images, I would contemplate right there. For example, if an image of the face arose, then I would contemplate the face. I would contemplate the senses of the face, such as the faculty of sight, as anatta. Investigating this ‘body within the body' ('Body within the body', that is, the experience of the body and sensory contact from the 'inside' as elementary feelings or, in other words, the body and sensory contact experienced as they present themselves directly to inner awareness), a mental representation of attachment between the senses and their objects arose within the mind, perceived as a network of white nerve-like filaments. This ‘sensory web', in which each filament was different, then disintegrated as anatta. Whenever I perceived an attractive object to which I was attached, then this ‘sensory web' would manifest within my mind and I would contemplate all these attachments as anatta. That is to say, whenever these mental images arose within the mind, I would contemplate that aspect of my body or the female body that I was attached to in these visions causing it to disintegrate and become empty of self.

I repeatedly investigated this subject until the end of February. Sometimes, I would see the body as anatta, shattering apart. Within the mind there were mental images of both the beautiful and the repulsive. The repulsive mental images were those I had created to oppose those other images within the mind that I perceived as beautiful. Internally, I had fully developed the perception of the repulsive to counter and correct the memories and perceptions of beauty in the mind. I contemplated all these memories and perceptions as completely anatta. I was no longer fixated upon these memories and perceptions whether of the beautiful or the repulsive because, although they are real and exist within the mind, their reality is impermanent, stressful and without a self.

As I contemplated both these conditions - the beautiful and the repulsive - as anatta, I knew that I had brought my practice of asubha kammatthana to completion. I was no longer swayed by the perceptions of beauty created within the mind because the heart could now balance them with perceptions of the repulsive in an even match. Consequently, the heart became bold and confident.

Although subtle attraction still arose with sensory contact, it was not necessary to analyze external forms because this attraction was too refined to contemplate in this way. When the eye contacted forms, for example, subtle desire would arise and so the mind would note down that sense object and store it away as a memory. When I sat in meditation, these memories would arise and the mind would create perceptions of the repulsive to counterbalance them. Therefore, during this period in February 1984, it no longer became necessary to investigate externally. There was no need to contemplate objects outside of myself. I only needed to put forth effort to maintain mindfulness and samadhi. When I was peaceful, the heart would destroy these mistaken perceptions of beauty all by itself. Consequently, the heart became much more free and at ease than before.

On the 20th of February, I was sitting in meditation when a nimitta arose. On that day, the mind was most extraordinary having been calm for many days previous. As I was meditating, a mental image of a person arose. However, when the mind focused upon it, this nimitta began to rotate. The mind then focused back upon my own body using this rotating image to uproot the perception of self With my eyes closed, I saw a mental image of my body spinning lii"'e a top or a tornado. As it whirled around, I saw the four elements spinning together, merging into unity, until finally shattering and scattering into fragments. The mind saw the body as anatta; it realised that this physical form is not a self.

On February 20th, the practice of asubha kammatthana and the investigation of the elements were brought to completion. On that day, the practice brought visible results, a realisation that came through the investigation of asubha kammatthana and contemplation of the elements. Following on from this, the heart began to change once more, but the change was not yet complete ... The Path though, was steadily ascending higher and higher.

While meditating one day in April, the mind entered samadhi and became completely empty. Both the breathing and hearing ceased. The mind was very refined, entering into complete emptiness. This had never at all happened before. After the mind had emerged from this state, the body was seen as completely empty. The mind automatically separated from the body which then disintegrated all by itself in a way that was considerably more refined than ever before. Everything was seen as completely empty. Trees, mountains, monasteries, meeting halls - all of them empty. Even when these things were not conventionally speaking, ‘empty', the heart, through the power of samadhi, clearly knew that they were of the nature to be empty. With samadhi completely firm, ‘the knowing' manifested as wisdom. Together, samadhi and wisdom bring results in this way.

With this experience of emptiness, there was a deeper understanding of the Dhamma and the nature of this physical body. Greed, hatred and delusion were eradicated on a much more refined level than before. The heart had entered the state that the Krooba Ajahns call ‘appana samadhi'. This is the basis for wisdom and vipassana to arise. When the heart had reached this stage, I knew that this was what the great teachers referred to as appana samadhi. Entering into this state, the breathing had ceased. The heart was fully absorbed. The mind was empty of self. After withdrawing, having realised this state, the heart experienced considerably more bliss and contentment than on any other occasion in the practice up to that point. The heart had increased in refinement and profundity once more.

After contemplating anatta through the power of appana samadhi, the heart can sometimes remain in this state of emptiness for six or seven days. If a person is deluded or not fully aware, they might grasp this state - as long as it does not degenerate - to be that of the Arahant. I have seen others who, experiencing this state of emptiness, mistakenly take it to be that of the Arahant. On this occasion, my heart did not remain in this state for very long. It withdrew to continue investigating the body. This was because I had not been constantly training in only the aspect of samadhi. Mostly, I would only use the power of samadhi to contemplate the body so as to uproot the perception of self. Consequently, this state of appana samadhi did not sustain itself for very long and so I did not become stuck there.

As I continued to practise, my mind became wondrous. After withdrawing from meditation, many insights into ultimate reality (Sabhava Dhamma) would arise. Sometimes, observing the breath coming in and out, the mind would know that the body is anatta. Sometimes, the body would be seen as though it were a coating of rust flaking away; as not-self. At other times, the body would be seen with insight into each layer of the skin, beginning with the outermost and reaching right down to the bones, this awareness piercing straight through the body and out the other side. Investigating the body over a period of ten days, each layer was seen as anatta.

When sitting in meditation, the mind would focus upon the skin, penetrating through from the outermost to each and every layer. It was as though awareness passed through the body in a flash, seeing it all in fine detail right down to the bones before shooting through outside. This body would then be seen as anatta. This is called the arising of insight into ultimate reality. Due to the power of samadhi, the mind took-up these insights as its object so as to uproot the desire and aversion towards the body. The nature of this Dhamma that arises will be different for each person depending on the strength of their spiritual maturity (parami)or previous training. These insights into ultimate reality arise only to enable us to understand that the body is anatta; neither a self nor a soul.

Following on from this, entering the month of May, although there was awareness of attraction and repulsion towards contact with external sensory objects, these perceptions no longer had any power over the mind. Although these perceptions remained within the mind the same as before, their impermanent nature had been seen. They would arise and cease with great rapidity and the desire that arose in conjunction with these perceptions, of beauty for example, would also suddenly cease. Mindful awareness of the arising and ceasing of this desire and aversion was automatic. Even though the memory would still implant these perceptions deep within the mind as before, the mind was bold and unwavering because they no longer had any power over it. When the mind was calm and still, it could balance these perceptions of attraction and repulsion all by itself.

When the mind was peaceful, wisdom would arise, sometimes contemplating and seeing the body as anatta, sometimes contemplating kamma. I would see that all beings are the owners of their kamma and must experience its results. That is to say, when they act upon intention, whether skilfully or harmfully, all beings are the owners of their actions. This kamma does not belong to another and its results must be experienced. Whether beings experience happiness or suffering, it is just because of their kamma bearing fruit. Seeing into this matter, it provided instructive material enabling the heart to let go of attachment; to abandon its fixation on the body - just this much.

I continued practising in this way until June, gaining insights into ultimate reality, and training the heart to see anatta. On the day before Luang Por Chah's birthday, many monks and novices had gathered at Wat Nong Pah Pong to pay their respects to the teacher. In the evening, as they pushed Luang Por outside in his wheelchair, my mind converged and so I closed my eyes. As soon as the eyes opened again, I saw Luang Por and all those sitting around him with insight in terms of the three characteristics. I saw that the monks and novices, right down to myself, were all of the same nature. The mind then saw the body disintegrate as anatta.

The contemplation of the body and the realisation of anatta on that day, June 16th, was another factor that enabled the heart to increase in profundity and refinement. However, the heart's affair with the body was not yet over once and for all. There was still attachment to the body but this attachment was very subtle. The fact that these insights into ultimate reality had manifested at all was because my heart had been gradually removing the attachment to the body. Sometimes I would clearly see the body as anatta, at other times, people were perceived as though they were my mother (Meaning there were no longer feelings of attraction or aversion), and on yet other occasions, women were perceived as men.

Following on from this, I had feelings of profound weariness towards all experience of the sensory world. I felt deep disenchantment towards all sensory experiences, whether sights, sounds, odours, flavours or bodily sensations. I wished to be completely free from attachment to these things once and for all. The heart had no wish to be bound up with sensory experience. I continued to practise in this way until the end of June 1984.

In as much of my practice as I have related here, in conclusion, it is enough to say that I put forth effort, keeping a solid foundation in si1a. As a layman I practised generosity. I would consider; "My life is uncertain, whereas death is a certainty. I surely will have to die; my life will end in death. If death is coming, then what's the point of amassing wealth and possessions? Regardless of how much I make plans to save, or become self-made and secure, life is uncertain. Sometimes the money and assets that I have sought out are not even put to use." Consequently, I tried to practise dana and establish myself in this quality of generosity and self-sacrifice. I gave freely of my resources on a regular basis until, one day, I asked myself why I was working considering I gave most of my monthly wage away as gifts or offerings using only the little that remained to support myself. I reflected; "What's the reason for working if I give away all that I make? Its better I ordain and seek freedom from suffering."

I put forth effort in practising generosity to establish myself in noble spiritual qualities. When I performed deeds of generosity, gradually the heart became more self-sacrificing and the power of selfish greed was restrained. Consequently, my heart conceived the wish to ordain; I no longer wanted to earn a living. A worldly person would call such individuals feeble, labelling them as life's losers. However, for those following the way of Dhamma, such wishes and wants are called, `seeing the danger in the cycle of death and rebirth.' The danger is seen in that, although our good deeds lead on to goodness, acts of evil plunge us down the abyss to a hellish birth, becoming animals, demons or hungry ghosts, where there is total suffering and misery. Consequently, not taking birth is more favourable. It is better to seek freedom from suffering, to strive in the quest for liberation.

I will soon be travelling to Rayong Province and will probably takeup residence there. As a monk and a samana refraining from the pursuit of wealth, I have nothing except the Dhamma teachings of the Lord Buddha and my own practice of meditation with which to repay the kindness of all the lay supporters here at Lamlukka. Every one of you faithful devotees has always made your best effort to attentively support the monks and novices. If I had not sincerely practised, it is likely I would be unable to repay this karmic debt. Initially in my practice, aware of this indebtedness, I was wary and apprehensive when I saw faithful supporters bringing the four requisites (the basic supports of life - food, shelter, clothing and medicine) to offer. However, I tried hard practising to make myself noble and worthy so that all my supporters would find peace and contentment Consequently, seeing the faith of all the lay supporters here at Lamlukka, I rejoice in your goodness and in your wholesome aspirations.

Finally, may the power of the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha aid an assist all of you sitting here, and all those who come to make merit here at Lamlukka. May your hearts be calm and serene, firm in samadhi, shining bright. May you all abandon evil, do that which good and purify the heart, freeing it from suffering and arousing the vision of Dhamma.

© 2006 by Wat Marp Jan Cover art by Aleksei Gomez This book has been sponsored for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma and may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any format, for commercial gain. Permission to reprint for free distribution can be obtained from: Wat Marp Jan, Klaeng, Muang, Rayong 21160, Thailand.

|

|

|

|

|

| Home | Links | Contact |

Copy Right Issues © What-Buddha-Taught.net |