|

Developing Samadhi |

|

|

|

|

|

© 2006 by Wat Marp Jan Cover art by Aleksei Gomez This book has been sponsored for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma and may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any format, for commercial gain. Permission to reprint for free distribution can be obtained from: Wat Marp Jan, Klaeng, Muang, Rayong 21160, Thailand.

Translators Introduction This book aims to serve as an introduction to the Dhamma teachings of Venerable Ajahn Anan Akincano. These teachings provide both a guide to the fundamentals of meditation practice and also an overview of the entire Noble Path from beginning to end. Both these aspects stress not only the development of samadhi and wisdom, but also the cultivation of other essential virtues such as generosity, patience, loving kindness and moral discipline that together emphasise the integrated and harmonious nature of the Buddhist path. Ajahn Anan is a distinguished first generation disciple of Venerable Ajahn Chah Bodhiyana Thera (1919-1992), who was a spiritual mentor and 'teacher of teachers' revered throughout the Buddhist world and one of the most influential Theravadan bhikkhus of recent times, both inside and outside his native Thailand. After the passing away of Ajahn Chah, who was affectionately called Luang Pu or Venerable Grandfather, it seemed natural that Ajahn Anan, as an accomplished student of this celebrated Master, should begin to exert a similar influence over a new generation of Buddhists, who look towards him for guidance and inspiration. The teachings contained within this book were originally extemporaneous talks delivered to mixed audiences of both monastics and laity without any formal planning in advance, as is the style of meditation teachers in Thai forest monasteries. Pali, the scriptural language of Theravada Buddhism, is used sparingly in the first two talks and often the meanings of those terms used are explained in the text anyway or can be inferred from the context. However, in later talks these Pali terms are employed much more freely with the hope that they will deepen readers understanding of spiritual practice. With this end in mind, a comprehensive glossary is included at the back of the book. Often the effort to penetrate the meaning of these terms can instill a sense of faith and wonder at the profundity of the Buddha's teachings, and guide one's practice of meditation towards their realisation. Indeed, the Pali language serves no other purpose than to clarify the path of spiritual development in a coherent and systematic way. Used as such, the Pali language, like any other tool, can greatly enhance one's understanding and ability to succeed at the task in hand, in this case, the liberation of the heart from all suffering and stress.

Developing Samadhi

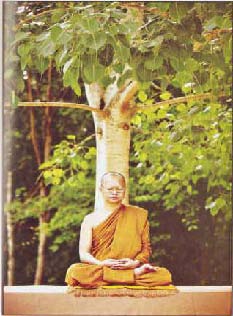

A guide to the fundamentals of meditation by Venerable Ajahn Anan Akincano

"Ordinarily, our mind is ceaselessly thinking and fantasising. To halt this flow of menta proliferation we need to practise meditation." When sitting in meditation we assume a posture that feels just right, one that is balanced and relaxed. We should lean neither too far left nor too far right, neither too far forward nor too far back. The head should be neither raised nor drooping and the eyes should be closed just enough that we don't feel tense and uptight. We then focus awareness upon the sensation of breathing at three points: the end of the nose, the heart and the navel. We focus awareness, firstly, on following the in-breath as it passes these three points - beginning at the nose, descending through the heart and finishing at the navel- and then, secondly, on following the out-breath in reverse order - starting at the navel, ascending through the heart and ending at the tip of the nose. This preliminary means of focusing awareness can be called 'following the breath at three points'. Once we are mindful of the in-and-out breathing and proficient at focusing awareness on these three points, then we continue by clearly following the in-breaths and out-breaths just at the tip of the nose. We maintain awareness of the sensation of breathing by focusing on only the end of the nose. Sometimes, as we focus on the breathing, the mind wanders off thinking and fantasising about the past or the future, and so we have to put forth effort to maintain this present moment awareness of the breath. If the mind is wandering so much that we cannot focus our awareness, then we should breathe in deeply, filling the lungs to maximum capacity before exhaling. We should inhale and exhale deeply like this three times and then start breathing normally again. As the in-breath passes the nose we count, 'one'; as it passes the heart, 'two'; the navel, 'three'. With the out-breath we count 'one' as it moves up from the belly, 'two' as it passes the heart area, and 'three' at the nose-tip. We should count in this way until we are skilled and proficient. This is the first method of focusing awareness upon the breathing. Alternatively, we can focus our awareness using the second method of 'counting in pairs'. We count 'one' as we breathe in and 'one' as we breathe out. With the next in-breath we count, 'two', and with the out breath, 'two'. Then, in - 'three', out - 'three'; in - 'four', out - 'four'; in - 'five', out - 'five'. Firstly, we count in pairs of in-and-out breaths up to 'five'. After the fifth pair we start again at 'one' and increase the count of in-and-out breaths one pair at a time, for example: in-out, 'one'; in-out, 'two'; in-out, 'three'; in-out, 'four'; in-out, 'five'; in-out, 'six'. After counting each new pair of in-and-out breaths we start again at 'one' and increase the pairs incrementally up to 'ten'. Using this method we will be aware of whether our mindfulness is with the counting - totaling the numbers correctly - or whether it is distracted and confused. When competent at counting the breaths, we will see that the breathing is perceived with increased clarity. The rate of counting can now increase in speed as follows: with the in-breath we count, 'one two-three-four-five', and with the out-breath, 'one-two-three-four five'. When proficient at counting up to five like this, we can increase the number to six: breathing in count, 'one-two-three-four-five-six', and breathing out count, 'one-two-three-four-five-six'. Alternatively we can continue counting up to 'five', whichever feels more comfortable. We can experiment to see whether counting up to five is enough to hold our attention or not. If we cannot remain mindful and wander off into thoughts, then we should count rapidly on the in-breath, 'one-two-three-four-five', and similarly on the out-breath, 'one-two-three-four-five'. We should count in this way until we become skilled and proficient. Eventually, we will become aware that the mind has let go of the counting all by itself and feels comfortable knowing the in-and-out breathing just at the tip of the nose. This can be described as a mind brought to peace through the method of counting in pairs. If meditating at home, we begin by reciting the qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha. We can recollect these qualities by chanting the daily devotions to the Triple Gem either in full or in brief. We then generate thoughts of loving kindness directed firstly towards ourselves, reciting the verse, 'May I abide in well-being'. We then spread these thoughts of loving kindness to include all beings: 'May I they be happy and free from suffering; may they not be parted from the good fortune they have attained'. We focus next upon knowing the in-breaths and out-breaths at the three points, or according to the method of counting in pairs, as has already been explained. We establish mindfulness by focusing awareness completely upon counting breaths. When mindfulness has been properly established, then the heart will be continuously aware of the process of counting, recollecting nothing else, especially those mental objects conducive to sensual desire, ill-will, sloth & torpor, restlessness & agitation and doubt. When mindfulness has been properly established, these Five Hindrances do not arise. Concentration then becomes firmer and samadhi arises, characterised by a momentary peacefulness of mind called khanika samadhi. This is only a slightly concentrated state of mind. If we are focused in samadhi with continuous mindfulness, then sometimes the state known as piti will arise. Piti is characterised by physical sensations of coolness or of a rapturous energy thrilling throughout the body - like waves breaking on the shore - which can cause the body to sway and the hair to stand on end. These sensations are accompanied by mental perceptions of physical expansiveness. When mindful awareness is focused continuously, it can seem that the hands and feet have vanished. The feelings in other areas of the body, even the sensation of the whole body itself, can likewise entirely disappear from consciousness. The body feels completely tranquil. During this period that the heart is peaceful, the mind temporarily lets go of its attachment to the physical body and consequently mind and body feel light and tranquil. As we sit in meditation and this tranquility increases, it can seem as though we are floating in space, giving rise to feelings of happiness and well-being. At this point we can say that the power of our concentration has deepened to the level of upacara samadhi.

As samadhi deepens further, the heart experiences even greater rapture and bliss together with feelings of profound inner strength and stability. All thoughts completely cease and the mind becomes utterly still and one-pointed. At this stage we cannot control or direct the meditation. The heart follows its natural course, entering a unified state with only a single object of consciousness (ekaggatarammana). This is the unification of mind in samadhi; the heart has been stilled and brought to singleness.

Each of these levels of peace provides us with inner strength; they empower the heart for developing wisdom. When we contemplate the body through the modest peacefulness of khanika samadhi for example, then we will gain a modest degree of insight. Through investigation, we will clearly see that this body is impermanent. We can contemplate the nature of the body right from its beginnings. How did it look at conception? What was it like in the womb? We can consider the body's appearance as a child, gradually growing and maturing but always inconstant and changing. The sense organs - the eyes, the ears, the nose, tongue and physical body - gradually deteriorate with age along with the faculties of seeing, hearing and so on. When degeneration sets in to a greater degree, we say that the body is old. It then becomes sick and eventually dies.

When samadhi is strong then the heart is strong, capable of contemplating and clearly seeing the physical body as impermanent. The deeper the samadhi is, then the deeper the insight into impermanence. We clearly see the truth of the Buddha's teaching, that the body is anicca - dukkha - anatta; inconstant, stressful and neither a I f nor a soul. At this stage we are possessed of the deepest type of wisdom; we see the truth with a clarity that is neither questionable nor dubious.

There are three levels of wisdom and understanding. The first of these is the understanding acquired through learning or the wisdom which results from listening to and studying the teachings of the Buddha. The second level of wisdom arises through contemplation and investigation of the truth. The third and deepest level of wisdom is acquired through the practice of meditation. This is the wisdom that arises from a peaceful heart and sees things according to reality (These 3 levels of wisdom are known as suttamayapanna, cintamayapanna, bhavanamayapanna).

We practise mindfulness of breathing to make the heart peaceful. We can count breaths or use the additional mantra 'Buddho'; internally reciting 'Bud -' with the in-breath and '- dho' on the out-breath. When the heart is calm and concentrated, we can use the power of this samadhi for investigation because, even with momentary concentration, the mind is supple and at the stage where it can clearly contemplate the physical body and the mind, whether feelings, perceptions, mental formations or consciousness. When memories and perceptions arise for example, we can see that they are clouded and hazy, like a murky and overcast sky, incapable of penetrating to things as they actually are. Thoughts and mental formations are sometimes wholesome, sometimes unwholesome or else neutral, neither one nor the other. These sankharas have no abiding essence at all.

Consciousness refers to the awareness of knowing, seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touching. There are six classes of consciousness - based on these six senses (mind is the sixth sense) - arising and ceasing in succession. While listening to the Dhamma for example, if the ear and the faculty of hearing are normal and unimpaired, then we can hear what is being said. If this sensory apparatus has deteriorated, then the hearing will not be clear. Hearing therefore, is dependent upon sounds making contact with the ear and the faculty of hearing being in a healthy state. When we hear sounds there is also the awareness of 'hearing'; the mind is conscious of hearing sounds. However, we attach to this awareness and identify with the hearing as one's self, that is, 'I hear' or 'hearing belongs to me'.

The process of hearing is dependent upon many causes and conditions. If there are no sounds, then there is no experience of hearing. If there is no contact between the ears and sounds, then likewise, there is no experience of hearing. If the faculty of hearing is impaired, then we feel that we haven't heard properly. Therefore, when there are sounds, the faculty of hearing is unimpaired and there is contact between these sounds and the auditory sense base, then consequently ear consciousness arises and hearing takes place. The same is true of the other senses.

Without exception, all these six classes of consciousness that arise by way of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind are merely types of elements (e.g. ear-consciousness element (sotavinnanadhatu). If our heart is peaceful, then we will see all these types of consciousness as just elements arising and ceasing, without a self or soul. In reality, the self is like a conjuror's trick arising and passing away at the six sense doors. However, the mind that lacks the inner strength of wisdom grasps onto the body, feelings, perceptions, mental formations and consciousness, and identifies with them as one's self. This attachment causes suffering to arise. When we have brought the heart to peace however, wisdom and the clear understanding that is called vipassana arises, enabling us to abandon this sense of self.

Therefore, in the beginning, it is essential that we practice meditation. We must train ourselves in present moment awareness in all postures using a preliminary meditation object to focus and guide our heart. Practising this way will greatly strengthen our mindfulness. We should put forth effort to observe our mind and feelings continuously. When there is contact between the senses and their objects - the eyes and forms, the ears and sounds, the nose and odours, the tongue and flavours, the body and physical sensations, the mind and mind-objects - we must mindfully contemplate how these sense objects effect our heart. The one who guards and cares for their heart will be liberated from all suffering.

We must look after our heart with mindfulness otherwise it will just grasp onto every object of consciousness, creating a sense of self. The untrained heart lacks the wisdom to see that this attachment causes suffering. Nobody wants to suffer but through this attachment to the objects of consciousness, stress and discontent always arise. Therefore, we have to train our heart following the way of the Buddha, who exhorted us to be mindful at all times, whether standing, walking, sitting or lying down. Focusing awareness on the in-and-out breathing is also a form of mindfulness practice called anapanasati - mindfulness of breathing. Every day we can focus our awareness through this practice for thirty minutes or, if we have more energy, for forty-five minutes or even for an hour. Whenever we have time, we should try to practise mindfulness until it becomes firm and focused continuously. When we are accomplished in mindfulness, concentration and wisdom arise. Whenever we are mindful, we are perfecting the factors of the Noble Eightfold Path. Right Effort means striving to develop mindfulness in the present moment, abandoning the past and the future. Right Effort also includes the effort to prevent unwholesome mental states from arising in the mind and the effort to evoke and maintain wholesome, skilful qualities. The factors of Right Mindfulness and Right Samadhi are also developed with and through the factor of Right Effort. As for those aspects of the Noble Eightfold Path concerning moral conduct, such as Right Speech for example, these are also developed through the practice of mindfully sitting and walking in meditation. While in meditation, our actions of body and speech are focused in a wholesome way and we are engaged in an activity that is skilful and pure, in accordance with Right Livelihood. By contemplating the hindrances to meditation, such as restlessness, and also reflecting upon how suffering is caused through attachment, we are developing the Path factors of wisdom, that is, Right View together with the Right Aspiration to be free from suffering once and for all. Therefore, all the components of the Noble Eightfold Path, or in short, sila - samadhi - panna, are perfected through the practice of meditation because while practising meditation, we are simultaneously developing all eight factors of the Path. Mindfulness can also be developed through walking meditation. We should walk with composure, the hands clasped lightly in front, right over left. The head should be neither raised too high nor hung too low. The eyes should be focused forward to an even distance and stray neither left nor right, neither behind nor too far ahead. While walking back and forth, we coordinate the movement of our feet with the mantra, 'Buddho'. As we step forward, leading with the right foot, we internally recite 'Bud -' and with the left foot, '- dho'. Luang Pu Chah taught that while walking in meditation, we must be aware of the beginning, middle and end of the path. While reciting 'Bud -' with the right foot and '- dho' with the left, we should also fix our mindfulness on knowing our movements in relation to these three points along the path, that is, as we begin, as we pass the middle and a we reach the end. Upon reaching the end of the path, we stop and establish mindfulness anew before turning around and walking back reciting, 'Bud - dho', 'Bud - dho', 'Bud - dho' as before. Focusing upon the activity of walking while pacing to-and-fro is called 'cankama' ([Thai] jong-grom) or 'walking meditation'. We can adjust our practice of walking meditation according to time and place. If space allows, we can establish a walking path twenty-five paces long. If there is less room than this, we can reduce the number of paces and walk more slowly. While practising walking meditation however, we should walk neither too fast nor too slow. When listening to others, we can also focus on reciting 'Buddho' in our heart while mindfully noting that we are listening. We should strive to be mindful whatever our activity, be it sitting, talking or listening. Luang Pu Chah greatly stressed the practice of mindfulness. When the heart is peaceful, we can turn to the contemplation of the physical body, feelings, perceptions, mental formations and consciousness. We will see that these Five Aggregates merely arise, exist briefly and then completely pass away. There is no real, abiding self or soul or person or being or 'me' or 'you' to be found. Although the Lord Buddha is referred to as the Enlightened One, He taught that we should not identify with this knowledge of the truth. Nevertheless, we can listen to and investigate the teachings without understanding that we shouldn't attach to our knowledge and insight. Because we still have self view and the desire to identify with our experience, we can become confused about how to proceed. The Lord Buddha taught that even with knowledge and a clear understanding of the truth, we should recognize this knowledge as being simply Dhamma arising, establishing itself and then passing away. The completely pure heart then arises. As we develop mindfulness, we can see that sometimes the heart is possessed by greed, hatred and delusion. Recognising this, we should also be aware that this is just the nature of the unenlightened mind. It is also just the nature of the mind to be, at times, without these defilements. The mind that is sometimes wholesome, sometimes unwholesome, sometimes bright, concentrated, blissful, calm and wise is also just the mind as it is, according to its nature, and not to be clung to as 'me' or 'mine'. The mind is just the mind, not a self or soul or person or being or 'me' or 'you'. Even this knowledge however, should be let go of. This insight that body and mind are not-self is called wisdom, but wisdom too must be let go of and relinquished. By training our heart this way, it becomes peaceful, pure and radiant. The mind that has been well trained naturally brings happiness. The untrained mind is a danger; it has no refuge and out of ignorance, continuously races along with its moods and desires. However, the mind that has been properly trained brings us happiness. Most of us have already received an education or some kind of training and are knowledgeable in the various arts and sciences of the world. However, we have to further train our minds to be peaceful and to recognise the danger of being immoral and undisciplined. We have to keep our actions of body and speech within the bounds of virtue and see the danger in the hindering defilements of desire and aversion, cruelty, ill-will, doubt, agitation and restlessness. As we learn to see the harmful consequences of such mental states, we develop loving kindness, aspiring towards the happiness of ourselves and others, freed from hatred and ill-will. Initially we cultivate loving kindness towards ourselves and those we love, such as our mother and father, and then we extend these benevolent thoughts to include beings everywhere. Through the cultivation of loving kindness we sleep well and our heart is peaceful. We then turn towards the contemplation of the body, feelings, mind and mind-objects (The Four Foundations of Mindfulness), seeing that these things are just that - body, feelings, mind and mind-objects - nothing more. They are neither a self nor a soul nor a person nor a being nor 'me' nor you'. Wisdom then arises and suffering steadily diminishes. Therefore, we must train and develop our hearts. If we do not train ourselves in this life, then we'll leave the world empty-handed. We have to study this physical body; it is born, gradually ages and eventually dies. It is evident therefore, that only suffering lays ahead, not happiness. Old age, sickness and death are waiting for us. At present we may not be aware of this process of degeneration, but later on it will become obvious. Our eyesight, hearing and physical strength will deteriorate. Some people have a long life but eventually they die of old age. When the body reaches its end and can no longer sustain itself, then we call this 'dying of old age'. When the body is at the point where it can just keel over and die, then we say it has reached old age. When very old, the body sickens and when very sick, it dies. At present we are still physically strong and can sit and walk in meditation with ease. We can practise mindfulness easily and should therefore, strive to train ourselves. Training the mind in meditation is much more meritorious than practising generosity and observing precepts. Therefore, whether living at home or in a monastery, we should put forth effort to train ourselves according to the methods that have been explained here. We should train our hearts in peace and then contemplate the truth to bring forth wisdom. We will then realise the fruits of practising Dhamma.

|

|

|

|

|

| Home | Links | Contact |

Copy Right Issues © What-Buddha-Taught.net |